An ocean apart

Both Edmonia and Samuel expertly navigated the first wave of American identity politics in the nineteenth century and its reactionary aftermath, by using art, self-fashioning, and entertainment to build communities across difference. A master of the neo-classical style, Edmonia upended many artistic and cultural norms. She infused American themes of freedom and individuality in her practice, sculpting subjects ranging from literary figures to her abolitionist peers. Her most famous sculptural subjects—Cleopatra and the biblical figure of Hagar—countered the era’s figurative stereotypes and connected these foundational stories of Western culture to the Black diaspora.

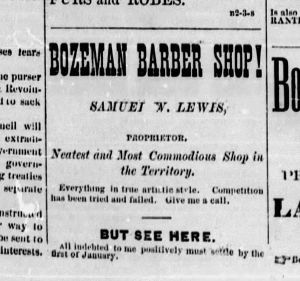

Chisel & Razor contributes to Edmonia’s growing art historical recognition by including Samuel, a foundational but largely forgotten figure in Montana’s past. Arriving to Montana in 1866, Samuel was a founding member of a Black settler community that flourished in Bozeman after the Civil War. A skilled barber and developer who became a prominent, respected community figure, Samuel was also an entertainer, who performed as a musician and magician delighting local audiences across the state. Tinworks is the first art institution to bring Samuel’s story to light, engaging contemporary artistic voices in dialogue with Montana’s local histories.

Samuel

Samuel W. Lewis (b. May 15, 1832; d. March 28, 1896) was born in the British colony of Bermuda just two years before Britain ended slavery. The contours of his early childhood remain shadowy, but he arrived in Newark, New Jersey, with his parents as a toddler. By fifteen, both parents had died, and, if his sister’s account is accurate, Samuel found himself alone, at a residential school “for Indian boys.” What he created from this early tragedy was extraordinary: a life of perpetual reinvention that would carry him across oceans.

Teenage Samuel traveled throughout New England with a circus, learning the dangerous arts of bareback riding and tightrope walking. Between performances, he worked as an itinerant barber, his hands skilled in two trades requiring steadiness and nerve. These skills afforded a future for his younger sister Mary Edmonia Lewis, funding her education even as he saved for his own journey west.

In 1852, Samuel joined the westward rush for gold, opening a barbershop on San Francisco's Telegraph Hill. But Samuel was never a man of single pursuits. In Sierra County's goldfields, he mined and performed, his banjo playing earning renown and a small fortune– $5,000 in gold, worth nearly $200,000 today. Like other West Coast performers, he likely followed the Pacific Circuit to Hawaii, Japan, and Australia, gathering stories and skills that would shimmer around him like an aura.

During the Civil War’s final years, Samuel sailed for Europe, studying sleight-of-hand with “an eminent French professor” in Paris. When he returned, his California fortune had vanished in bank failures, but Samuel simply moved forward. He opened a shop in Idaho City; it burned down on his birthday in 1865. He kept moving.

By 1868, Samuel had settled in Bozeman, Montana. Throughout his wanderings, he had been his sister’s ballast, funding her studies at McGrawville and Oberlin, supporting her Boston studio, helping pay for her 1865 passage to Rome. The siblings wrote every two weeks, their letters bridging the distance between a Montana barbershop and a Roman studio.

In Bozeman, Samuel transformed from traveling showman to respectable businessman and town father. He acquired his first Main Street property in 1870, opening a barbershop roughly where Altitude Gallery stands today. Over the next decade, he purchased South Side lots and built rental properties, two still standing across from St. James Episcopal Church, where Samuel worshipped.

The relationship between Samuel and Edmonia reversed Victorian patterns of gender and economics. Samuel’s wealth underwrote Edmonia’s artistic freedom; his stability enabled her mobility. When Edmonia needed funds for her monumental The Death of Cleopatra in 1876, money came through the estate of another Black settler, Lizzie Williams, Samuel’s close friend and business partner – a reminder that his networks of support extended beyond blood.

In 1882, Samuel married Melissa Lewis, adopting her five children and fathering Samuel Edkins Lewis the following year. Even as a family man, he never fully left the stage, performing with the Bozeman Dramatic Association and Lyceum he made a name for himself as a virtuosic musician. He formed a family troupe specializing in dancing and tightrope walking– the same dangerous art he had mastered as a teenager. For Samuel’s children, growing up when opportunities for young Black Montanans were narrowing, the stage offered something precious: a space for self-determination and economic independence.

When Samuel Lewis died in 1896, hundreds of Bozeman residents followed his funeral procession down Main Street, led by the mayor himself. He was buried in Sunset Hills Cemetery, built partly with funds from his performances. In death, as in life, Samuel continued caring for Edmonia, leaving her an inheritance that sustained her final years as a sculptor. His life had been a feat of balancing acts: between respectability and spectacle, settlement and movement, supporting others while carving out space for himself and his family. Almost two hundred years since his birth, this exhibition revisits and reclaims Samuel’s story as a part of our local patrimony and asserts his place in the pageant of American west.

Edmonia

Like Samuel, much of Edmonia Lewis’s early life remains mysterious. Scholars generally agree, however, that Mary Edmonia Lewis (b. July 4, 1844; d. Sep 17, 1907) was born in Greenbush, New York, to a free Afro-Caribbean father and a mother of Mississauga and African descent. Orphaned as a toddler, she was raised from age nine by her maternal aunts near Niagara Falls, who gave her the name “Ishkoodah” which she translated as “Wildfire,” and immersed her in Anishinaabe artistic traditions such as birchbark and porcupine quillwork, textile making, and storytelling. These early experiences shaped her lifelong connection to Indigenous art, fostering what she would later describe as an inherited desire “to make the forms of things.”

Lewis’s formal education began at New York Central College in McGrawville, where she entered antislavery circles and encountered figures like Frederick Douglass, John Brown, and Wendell Phillips. At Oberlin College from 1859-1863, she studied drawing and engaged with classical themes, creating works like Urania, the muse of astronomy. Yet Oberlin also brought violence. In 1862, she was accused of poisoning two white housemates, beaten by a mob, and acquitted after a public trial represented by the up-and-coming lawyer John Mercer Langston. The next year, prevented from graduating after another false accusation, she left for Boston.

In Boston, Lewis studied with sculptor Edward Augustus Brackett, seeking him out because “he made a bust of John Brown, who offered up his life for my people.” She rented a studio in the Tremont Building and began creating portrait medallions of antislavery heroes, selling them at abolitionist gatherings. Her early sculptures, including a statue of Sgt. William H. Carney and a bust of Col. Robert Gould Shaw, constituted what historian Martha S. Jones calls “war work,” through which Lewis claimed freedom and citizenship. Living in the Black activist community of Beacon Hill, particularly in the home of Edwin and Joanna Turpin Howard, Lewis participated in networks of transatlantic Black solidarity that sustained her career.

In late 1865, Lewis sailed for Rome, settling there in January 1866. “I was practically driven to Rome,” she later explained, “in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color.” In Italy, she forged friendships with American expatriate women sculptors and writers, including Harriet Hosmer, Florence Freeman, and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards.

Lewis’s Roman sculptures reveal the entwined nature of heritage and politics. Works like Forever Free (1867) celebrated the end of slavery in the United States by depicting emancipated figures as actively seizing freedom. Her Hiawatha series, including The Old Arrow Maker and Hiawatha's Marriage, drew on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s popular poem but centered Indigenous women’s agency and artisanal knowledge, countering narratives of vanishing peoples. Unlike her contemporaries, Lewis portrayed Minnehaha as an equal diplomatic partner, “holding things together” through community knowledge and practice.

After converting to Catholicism in 1868, Lewis deepened her engagement with religious themes, creating works like Moses and Hagar that explored biblical narratives of deliverance resonant with African American Christianity. Similarly, her monumental The Death of Cleopatra (1876), exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, demonstrated her technical mastery but also celebrated a woman’s self-determination and freedom from bondage in the context of America’s 100th anniversary celebrations. This year, 2026, marks the 150th anniversary of The Death of Cleopatra.

Lewis’s sculptures challenged several historical erasures, claiming the neoclassical tradition for Black and Indigenous North Americans, while asserting Egypt’s role as a source for western classical culture. She was committed to representing liberation and persevering against prejudice. Though she died in relative obscurity in London in 1907, Lewis crafted a legacy that resonated in the work of 20th century artists, like Meta Warrick Fuller, Augusta Savage, and Faith Ringgold. As this show attests, her sculpture continues to shape our understanding of how art can serve both as an expression of freedom, and a means to claim it.

Support

Tinworks Art gratefully acknowledges the generous support of VIA Art Fund for the production and exhibition of Edmonia Triumphalis by Auriea Harvey, and the Vilcek Foundation for their support of Sunflowers, to follow the wheat by Agnes Denes, an ongoing ecological intervention in Tinworks’ field. Major program support for Tinworks Art is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and Tinworks Founding Director’s Council. Additional support is provided by coal tax revenues allocated to Montana’s Cultural and Aesthetic Projects Trust Fund.